(This is Part IV of my publication that I have split into five for Substack.)

See: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part V

Parts 2 and 3 emphasised the historical role of private planning in the development and redevelopment of modern London, and argued that it had some of the benefits often claimed for regulated systems, such as responding dynamically to changing circumstances and solving externality problems. This chapter traces the role of the state in regulating the development of urban London, showing how state power changed in both degree and kind. It locates this change within the perceived failures of the market, technological changes and the general rise in statist thinking about public planning. In conclusion it discusses current failures of the planning system, identifying opportunities for reform in light of lessons from the great estates.

At approximately the same time in the early twentieth century, the rise of social housing, emergence of mass owner-occupancy and continuation of rent control caused a collapse in the leasehold system. In the interwar years, private developers built an astonishing three million homes, mostly on farmland around Britain’s cities.1 But by mid-century, new regulations and the lingering economic effects of the Second World War had reduced the market-built housing sector to a shell of its former self. The 1947 Town and Country Planning Act nationalised the right to build, while urban green belts limited the extensive growth of cities.

Over the intervening years the Conservative Party, in particular, has sought to liberalise the market. The conversion of public housing into private benefitted a generation of existing tenants but failed to spur the type of supply-led changes needed for housing costs to come down. The financial regulations brought in after the financial crisis are also seen by some to have further hamstrung younger potential buyers.

Regulation of construction before dispersal

The benefits of the private planning of development and redevelopment as practised by the great estates were shaped by the institutional context of Georgian and Victorian London. To outline that context is no easy task. Prior to the 1889 creation of the London County Council (LCC), municipal governance consisted in a maze of local ‘vestries’ following parish boundaries. Only the City and Westminster – the former more important in terms of both population and economic heft – were unified. The earlier Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW), created in 1855, pulled some public services together across the region, including new sewerage for areas not served by the existing City of London system. The MBW also carried out slum clearance and roadworks. Initially these occurred concurrently because its slum-clearance powers depended on roadworks or other improvements, though over the nineteenth century, various Acts strengthened those powers. But in general there was little local planning apart from private planning by landowners and/or developers.

Despite this, the development of the great estates and the freehold lands surrounding them did not take place in the absence of regulation. The national government regulated building in various ways – some rulers even tried to ban all construction of dwellings around existing London. As Nicholas Boys Smith explains:

Under pressure from London’s Mayor and Alderman, four successive monarchs and the Parliamentary Commonwealth all attempted to prevent building beyond the city limits. At least three Acts of Parliament, nine Royal Proclamations and innumerable Orders in Star Chamber and letters to and from the Privy Council attempted to ban the construction of new building within one, two, three or five miles of the City Gates and of Westminster (details changed over time).2

Based on other sources, Boys Smith argues that the 1660s transformed London: attitude as well as policy changed from regulating the principle of building to regulating its manner and method – a useful distinction.3

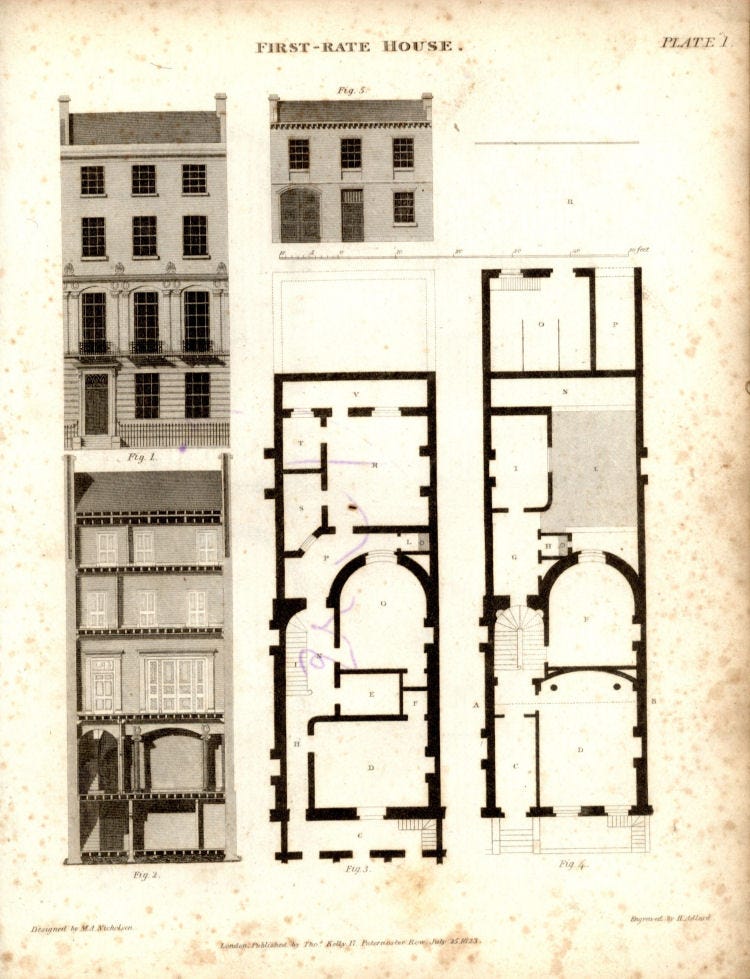

The Great Plague (1665) and Fire (1666) cleared the City of London itself of much of its medieval architecture. Although lofty plans for rebuilding along continental lines were drawn up, for a number of reasons they were not pursued.4 What did come about was the 1667 Rebuilding of London Act, which set out regulations for the City. These would ultimately be extended to Westminster and the rest of growing London, and included the standardisation of development into four ‘sorts’.5

In the aftermath of the Fire, various building Acts were passed to limit the types of building features that contributed to the spread of fire. Those of 1707 and 1709 banned wooden ornamentation, such as cornices, and stipulated that window frames be recessed – both in the interests of hindering the spread of fire.6 The entire system was overhauled in the late eighteenth century with the Building Act (1774), which applied to London and was extended to other cities.7 This introduced not only further regulations concerning exterior wooden ornamentation and the construction of windows but also a system of housing classification.

Under this, four ‘rates’ of houses related to the size of each floor and the type of street. For example, First Rate houses were defined as valued at over £850, with floorspace of more than 900 sq. ft,8 while Fourth Rate houses were valued at less than £150, with floorspace of less than 350 sq. ft.9 Alongside each rate sat different requirements for thickness of walls, among other things; but of major importance, as John Summerson and later writers agree, was that this system of regulation also ‘confirmed a degree of standardisation in speculative building’, so that references to rates became common in agreements between estates and builders.10

The first real overhaul of the 1774 legislation did not come until 1844, with the Metropolitan Dwelling Improvements Act. Over the rest of the century the tendency was towards measures increasing minimum street width and space between buildings, as well as decreasing density and addressing public-health concerns.11 Height restrictions were determined in part by the width of the streets and were strengthened in London after the construction of increasingly tall residential buildings along Victoria Street.12 In addition, the derived by-law regulations stemming from Public Health Acts increasingly regulated the form of housing in the UK, encouraging lower net density than earlier working-class housing as streets became wider. Over the second half of the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth, these types of control were tightened as demands for regulation continued, but other forms of state involvement grew alongside them. Nevertheless, Boys Smith13 notes that developments that met the rules could not be refused; there remained an implicit right to build.

Urban problems, slum clearance and overcrowding

By the middle of the nineteenth century the regulation of construction was just one aspect of state involvement in housing and housing markets:

Perceptions as to what constituted intolerable overcrowding varied between cases and between countries. England, almost certainly having the least congestion, was more concerned with overcrowding as an evil than either France or Austria and was far ahead of any continental country in providing philanthropic and municipal housing.14

Public-health crises, particularly those stemming from cholera epidemics, led to the state’s increased involvement. At first this meant more regulation, along with such public works as sewers and roads. Later it included clearance of the worst dwellings and ultimately provision of housing.

One way to view this historical development is to root it in the private philanthropic efforts of the model-housing organisations described in Chapter 2. These and other charitable providers achieved better outcomes through a combination of factors, only some of which were scalable. On the one hand, they built higher-quality housing and instituted practices both to guard against the deterioration that led to slums and to reduce turnover and improve rent-collection methods. They also set up paternalistic controls to limit social dysfunction. On the other hand, they also benefitted from being oversubscribed and so could select tenants in a way that, by definition, was not scalable. The very location of the charitable dwellings – that is, in the wealthier areas – was also carefully selected.15

Various factors conspired to keep the housing of the poor below an acceptable standard. Despite economic growth, incomes were still low. Furthermore, until the middle of the nineteenth century the geographic extent of an urban centre was limited by transport technology in a way it would not be later. Since the British economy industrialised early, it lacked cheaper, more remote housing for workers. When the railways arrived, their physical assault on the existing city went along paths of least resistance: as stations were built in London, as in other cities, they knocked out neighbourhoods that overwhelmingly housed the poor. Similarly the creation of roads by the MBW: sometimes rookeries or slums were targeted; generally though they simply represented the easiest routes along which to build.

These concerns were addressed in various ways during the middle and late nineteenth century by such legislation as the Torrens Acts (1868–82), which attempted to compel owners of slum properties to demolish or repair them, and the Cross Acts (1875, 1879), which allowed local authorities to prepare slum clearance and improvement schemes.16 This clearance also enabled philanthropic operators to acquire sites more cheaply.17 However, on balance it seems likely that all these measures ‘were largely destructive’, as Simon Jenkins illustratively writes, ‘acting as a many-pronged pincer squeezing the poor into even tighter corners of the city’.18

At the same time, the standards deemed acceptable for poor housing quality rose. While this occurred for what now seem obvious reasons, the effect was an artificial scarcity, with the maths of construction cost and ability of tenants to pay not working out favourably. Through various parliamentary reports and works by interested reformers such as Charles Booth, later Victorians developed a detailed sense of the plight of those who coexisted alongside their mannered middle- and upper-class domains. Within the broader historical and geographical context, urbanisation 19neither created poverty, nor was poverty unique to Britain or the nineteenth century. The captivating nature of nineteenth-century poverty in London and other urban centres was not its existence, rather its juxtaposition with wealth.

While the historical debate around standards-of-living changes associated with the industrial revolution, economic growth and urbanisation still rages, it is clear that standards did ultimately rise as a result of sustained economic growth. It is also clear that Dickensian nightmares notwithstanding, millions preferred living in the growing cities to remaining in the country.

Nevertheless, in an urban setting an aggregate of individual buildings of reasonable quality could suffer from problems of drainage and rubbish less likely to afflict rural dwellings, though such matters could be addressed through public works and improvements – as seen in the period properties that survived slum clearance. But for reasons including cost, public-health theories and ideological beliefs about density, the common response was that these were problems that better, lower-density housing would solve.

Planning, social housing and Nothing Gained by Overcrowding

According to James Yelling: ‘It is generally accepted that 1890–1914 was the formative period of modern British town planning, and henceforth the control of land, and of land uses and land values, became of heightened significance.’20

Already in the nineteenth century the idea that the dispersal of the population was the only way to improve their lot was becoming increasingly popular. Early forerunners of later government efforts include the Artizans, Labourers and General Dwellings Company on their Shaftesbury Park and Queen’s Park estates.21

Legislation in the nineteenth century allowed municipal governments to build social housing, the first example being in Liverpool under an 1864 Act.22 Most publicly supported – if not publicly provided – working-class housing came via the philanthropic model-dwelling providers, who were given land acquired by the MBW and later the LCC through their slum-clearance powers.23 However, this proved expensive and inefficient for housing the working classes.24

Instead, the direction of travel was towards suburban solutions for the working class, as increasingly for the middle. The transportation innovations described in Chapter 2 increasingly allowed the middle classes to choose a suburban and commuting lifestyle, but until 63 the twentieth century the combined cost of rent and fares proved unaffordable to most of the working class. One attempt at addressing this was workmen’s trains (in part required by Parliament), which offered reduced fares on early-morning journeys into London.25

Building first on examples from philanthropic model housing in London and later on visionary employee housing for industrial workers first at Saltaire and then at Cadbury’s Bourneville, public-housing efforts concentrated on urban tenements and, later, suburban cottage- style estates. As Richard Dennis writes: ‘Under Part III of the 1890 Housing Act local authorities were authorised to acquire green-field sites for public housing, and under a further act in 1900 these powers were extended to include land outside their boundaries.’26 The LCC’s four pre-1914 cottage estates were early examples of a type of local- authority development increasingly seen, after the First World War, as the way to provide better working-class housing. Private markets were not deemed able to provide such housing – a view helped little by wartime measures such as rent control, as well as the general post-war economic situation.

The political demand for improved housing was multifaceted and strong. The state of housing that soldiers returned to became a major point for the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. One perceived threat was political stability in light of the nascent Bolshevik experiment. The idea was that improvement of living standards and decentralisation and suburbanisation of housing would reduce political risk.27 As Peter Hall writes, the scale of the increase in state provision from before the war was remarkable, and between ‘1919 and 1933–4, local authorities in Britain built 763,000 houses, some 31% of the total completions’.28 The urban character of these places as well as private, owner-occupied housing for the better off stemmed from the ideas of the garden city and suburb of Ebeneezer Howard, Raymond Unwin and his influential Nothing Gained by Overcrowding and the resulting Tudor Walters Report. The standards promoted, 64 including ‘terraces of no more than eight houses (which often led to culs-de-sac) and a density of twelve homes per acre’, were only plausible on cheaper rural lands.29

The march of planning continued through the interwar years as Britain adopted American/German-style zoning with the Town and Country Planning Act (1932), which ‘introduced “Planning Permission” into British legal history’.30 As Boys Smith rightly notes, the plans passed during this time – like zoning in much of the USA before the 1960s wave of reductions in allowed housing – were more than adequate for population growth even at the low densities stipulated. But there were peculiarities to UK planning. The past changes in the role of the state in housing represented an ever stricter rules-based system paired with increasingly active state provision, though later the regulatory system became the more discretionary one that has endured into the twenty- first century.

London in the crosshairs and the countryside protected: town and country planning

Up through the interwar period the pattern of economic activity had been primarily market-based. Transportation developments enabled middle-class movement to new suburbs, while government policies worked towards the same end for the working classes. But there was no comprehensive regional or urban planning. This changed in the aftermath of the Second World War. The new goals of post- war planning included regional economic planning and countryside protection. Regional planning sought not just to support declining regions but may have also cut the ground from beneath the most successful cities. This targeted not just London but also the Midlands.31 Changing economic forces and trade patterns weakened the once mighty northern industrial cities, while the south-east, due in part to 65 rising industrial fortunes in the areas around the North Circular in London and out west towards Slough, continued to grow. For some intellectuals, regional divergence and the swallowing up of countryside and fertile farmland – as well as increasing probability of another war – together cast a shadow over London’s buoyant prospects. As Peter Hall describes, the intellectual history of urban planning is intimately tied to economic ideas and the romance of dispersal in the form of regional economic planning. Such planning manifested itself as distribution of industry and commerce as well as of housing.32

A number of legislative Acts in response to the Barlow Report of 1940 dramatically changed the political economy of Britain. Not just the more famous Town and Country Planning Act (1947) and the New Towns Act (1946) but also the Distribution of Industry Act (1945) created a system whereby an entire category of decisions moved from the market to planning experts. With the 1945 Act, the government required industrial development certificates from the Board of Trade for new factories or extensions over a certain size.33 A similar control was later applied to office space. The purpose of the first two Acts mentioned was to alter the political economy of housing development dramatically. At a fundamental level the right to develop land was nationalised with the Town and Country Planning Act, which also made it easier for local authorities to designate green belts as part of their development plans. Any development incurred a 100 per cent betterment levy, though this was dropped. With the New Towns Act the hope was to start dispersing the population of inner London into planned low-density towns.

In addition to these changes, as well as bomb damage, millions of houses in old neighbourhoods vanished in slum-clearance efforts, many replaced by council housing. Over time, especially in London and other cities, this came to consist of towers that residents disliked compared to other types of housing, and which achieved lower densities due to the vast open spaces around them. Furthermore, costs associated with added floors increased non-linearly, so they were more expensive than other types of more popular, denser housing.

Greater and greater London

The result of these policies and of changes in the British economy over the last decades has been to force development in the most productive places in the UK farther out (when it is allowed by the discretionary planning system) and to prevent the intensification of existing neighbourhoods (except for notable quasi-public regeneration projects in the last few decades). Importantly, the economic result of this is twofold: first, productivity improvements that do occur increase nearby land prices; second, productivity itself is limited because the extent of the labour market is constrained by land-use regulations.

When workers in a location become more productive they produce more output for given inputs. It is this productivity that drives economic outcomes. In the abstract, the expected responses to productivity effects are manifold. First, employers will want to locate in more productive places. Second, employees will be drawn to them because they can pay higher wages. The result is that productive places will become denser with workers and locations near them more populous. An example from the USA is Willesden, North Dakota, where fracking led to a boomtown in the last decade. In the short run, when the supply of housing is fixed (it takes time to build), the price would probably be expected to rise – a relatively small number of existing units are being competed for by productive and therefore well-paid workers. However, in the long run the market would be expected to determine the price of housing – not just ability to pay but capacity of sellers to provide. Just as in any other market, the lure of profit draws investors to finance and build because sale prices exceed land and construction costs. If, however, the supply of housing is entirely fixed by regulation, all gains in productivity will accrue to existing landowners.

While the actual situation is not that dire, interventions that limit the ability of housing supply to respond to price signals – that is, limit its elasticity – sap the real benefits of productivity. Rather than just being a distributional question about how policy changes the beneficiaries of enhanced productivity, policy also creates deadweight loss whereby the total wealth of society is reduced. By limiting the supply response, fewer people move to productive places, with dynamic effects on productivity itself. In a world with fewer regulations limiting housing, the resulting increase in labour in productive places would increase the wealth of both individuals and the nation as a whole.

(This is Part IV of my publication that I have split into five for Substack.)

See: Part V

Peter Hall, Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design in the Twentieth Century (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 1988), p. 79.

Nicholas Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’ (London: Legatum Institute and Create Streets, 2018), p. 56; https://www.createstreets.com/wp-content/ uploads/2018/11/MoreGoodHomes-Nov-2018.pdf

Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’, p. 57, drawing on Norman Brett-James, The Growth of Stuart London (London: London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 1935), p. 304.

Michael Hebbert, London: More by Fortune than Design (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 1998), pp. 23–6.

Referred to as ‘sorts’ in 1666–7 and later as ‘rates’; see https://www.british- history.ac.uk/statutes-realm/vol5/pp603-612#h3-0007

John Summerson, Georgian London (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 1945), pp. 53–4

Summerson, Georgian London, pp. 123–7

Summerson, Georgian London, p. 124.

Summerson, Georgian London, p. 125.

Summerson, Georgian London, p. 125.

Roger Harper, Victorian Building Regulations: Summary Tables of the Principal English Building Acts and Model By-Laws 1840–1914 (London and New York: Mansell, 1985).

Richard Dennis, ‘“Babylonian Flats” in Victorian and Edwardian London’, The London Journal 33:3 (November 2008), pp. 233–47; https:// doi:10.1179/174963208X347709.

Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’, p. 61.

Donald J. Olsen, The City as a Work of Art: London, Paris, Vienna (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 1986), p. 179.

Richard Dennis, ‘The Geography of Victorian Values: Philanthropic Housing in London, 1840–1900’, Journal of Historical Geography 15:1 (January 1989), pp. 40–54; https://doi:10.1016/S0305-7488(89)80063-5.

Peter Hall and Mark Tewdwr-Jones, Urban and Regional Planning (London: Routledge, 1975), p. 16

Richard Dennis, ‘Modern London’, in The Cambridge Urban History of Britain: Volume 3: 1840–1950, ed. Martin Daunton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 113

Simon Jenkins, Landlords to London: The Story of a Capital and its Growth (London: Constable, 1975), p. 185.

Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’, p. 59.

A. Yelling, ‘Land, Property and Planning’, in The Cambridge Urban History of Britain: Volume 3: 1840–1950, ed. Martin Daunton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 478.

Andrew Saint, London 1870-1914: A City at its Zenith (London: Lund Humphries, 2021), pp. 82–3; Dennis, ‘Modern London’, p. 33.

Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’, p. 62.

Dennis, ‘Modern London’, pp. 112–14.

J. A. Yelling, ‘L. C. C. Slum Clearance Policies, 1889-1907’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 7:3 (1982), p. 292; https://doi:10.2307/621992

Simon T. Abernethy, ‘Opening up the Suburbs: Workmen’s Trains in London 1860–1914’, Urban History 42:1 (February 2015), pp. 70–8; https://doi:10.1017/ S0963926814000479.

Dennis, ‘Modern London’, p. 114.

Hall, Cities of Tomorrow, p. 73.

Hall, Cities of Tomorrow, p. 76.

Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’, p. 62.

Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’, p. 62

John Myers, ‘The Plot against Mercia’, UnHerd, September 2020; https:// unherd.com/2020/09/the-plot-against-mercia.

Hall, Cities of Tomorrow, pp. 83–8.

Hall and Tewdwr-Jones, Urban and Regional Planning, p. 67.